Laryngomalacia also called “Dis-coordinate pharyngo-laryngomalacia” is the most common congenital lesion of the larynx (60-70%) and is the most common cause of congenital stridor in neonates and infants.

The condition is characterized by partial or complete obstruction of supraglottic laryngeal structures on inspiration because of excess mucosa, abnormal and/or reduced laryngeal tone.

The term laryngomalacia was coined by Jackson and Jackson in 1942.

Epidemiology & Etiology

The condition most commonly affects male babies with a male: female ratio of 2:1.

The exact etiology of laryngomalacia is unknown. Three theories are proposed to explain the pathogenesis.

- Anatomic theory: The cause of laryngomalacia is abnormal shape and structure of larynx. Manning et al found that a mean ratio of aryepiglottic fold/glottic length of patients with severe laryngomalacia was significantly lower than controls without laryngomalacia.

- Cartilaginous theory: the delay in maturation of supporting laryngeal cartilages, causes an inward collapse of supraglottic structures on inspiration.

- Neurologic theory: This is the most recent one and most accepted one. Neurosensory dysfunction leads to a lack of neuromuscular support to pharyngolarynx resulting in weak laryngeal tone is considered to be the etiology. This theory of altered nerve function was supported by the studies of Munson et al, who observed that nerve perimeter and surface area of superior laryngeal nerve branches within supra-arytenoid tissue of children with laryngomalacia are greater compared with age-matched autopsy tissues.

Clinical features

The typical clinical presentation is noisy breathing (stridor) at or shortly after birth (2-4 weeks), most commonly in premature babies.

The stridor is a high pitched, fluttering inspiratory one, which worsens when the infant is in a supine position, during feeding, is active or upset and disappears on sleeping.

The severity of stridor increases as the child becomes active for the first 9 months and then gradually diminishes, disappearing at the age of 2. On average, stridor resolves by 8 months of age. Very rarely stridor may persist into late childhood.

Feeding difficulties will be another complaint, because of the disruption in a delicate balance between suck-swallow sequence and respiration.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is strongly associated (70% of patients) with laryngomalacia because of the high negative intrathoracic pressure and also may be due to defective lower esophageal sphincter tone. Symptoms of GERD like aspiration, coughing, choking, regurgitation with feeds, slow oral intake, etc. may be present.

Differential diagnosis

Other causes of stridor must be considered when evaluating a child with these symptoms. These include vallecular cyst, epiglottitis, tracheomalacia, vascular anomalies, subglottic stenosis /cyst/hemangioma, vocal cord paralysis, laryngeal web, papillomatosis, etc.

One of the most useful ways to differentiate between causes of stridor is to identify in which phase of respiration the sound is heard. Different causes of airway obstruction cause stridor during different phases of respiration. In laryngomalacia, the stridor will be typically in the inspiratory phase of respiration.

Diagnosis

Proper history should be obtained with a focus on antenatal, natal and postnatal events as well as current symptoms. Prenatal complications, gestational age at birth, birth weight, history of endotracheal intubation, ICU admissions, etc. should be noted.

Special attention should be given on the child’s weight gain, feeding problems, feeding time, reflux symptoms and any history of pneumonia. Infants who have significant apnea/desaturations and/or inability to feed may warrant inpatient admission.

Infants with apnea, tachypnea, cyanosis, failure to thrive, difficult to feed despite acid suppression/texture modification, aspiration/pneumonia, cor-pulmonale should need an urgent evaluation by an otolaryngologist.

Complete physical and clinical examination should be done including general appearance, vitals, the weight of the child, presence of stridor, work of breathing – the presence of suprasternal retractions or abdominal muscle usage should be done. Auscultation of lung fields should be done, and the character of stridor should be identified. The presence of any chest wall abnormalities like pectus excavatum should be noted.

A digital X-ray / computed tomogram chest can be obtained, to rule out any associated airway anomalies. Those infants who may be aspirating and/or have pulmonary disease may benefit from chest x-ray to further evaluate this.

A Flexible fiberoptic naso-pharyngo-laryngoscopy (NPL) can be done to confirm the diagnosis and is enough in most patients. NPL is found to have 88% reliability for the diagnosis of laryngomalacia. The anatomic abnormalities observed during NPL scopy in laryngomalacia are:

- Long, tightly curled, soft epiglottis which is omega (Ω) shaped.

- Retroflexion (posterior displacement) of epiglottis

- Tall, bulky and Antero posteriorly short aryepiglottic fold, tightly tethered to the epiglottis.

- Tall, narrow and deep supraglottic inter arytenoid cleft.

- Supraglottic collapse – the long epiglottis, redundant mucosa and submucosa of aryepiglottic folds prolapses medially into airway obscuring evaluation of subglottis.

- Aspiration, pooling of secretions, and decreased supraglottic sensation may be seen during endoscopy in the setting of uncontrolled laryngopharyngeal reflux or neurologic disease.

Examination of larynx, trachea, and bronchi under Anesthesia (EUA laryngo-tracheo-bronchoscopy) under spontaneous breathing can be done when the child is having severe stridor, absence of any abnormality on NPL, failure to thrive, symptoms of aspiration or any atypical features. In 20% cases, other associated airway abnormality may present and in 5% cases, it may be clinically significant.

Other tests like modified barium swallow or functional endoscopic evaluation of swallowing may be considered, particularly if the concern of aspiration exists.

An esophagoscopy is also recommended to exclude any associated reflux disease and co-existing eosinophilic esophagitis that may lead to suboptimal outcomes for treatment.

Classification of laryngomalacia

Many classification systems are proposed for laryngomalacia, but no single system has been universally accepted. Modified Holinger Classification is the most commonly accepted system for laryngomalacia.

| Type 1 | The inward collapse of aryepiglottic folds on inspiration |

| Type II | Curled tubular epiglottis with short aryepiglottic folds, which collapse circumferentially on inspiration |

| Type III | An overhanging epiglottis, that collapses posteriorly, obstructing laryngeal inlet on inspiration. |

If surgical intervention is needed, the classification of anatomic site of supraglottic collapse can help in directing the surgical approach. There are 4 main categories:

- Posterior collapse: primarily caused by redundant arytenoid mucosa and/or excess cuneiform cartilage that prolapses into the airway.

- Lateral collapse: from foreshortened aryepiglottic folds

- Anterior collapse: obstruction from retroflexed epiglottis

- Combined: 2 or more of the patterns coexistent

Treatment

In 90% of cases, no intervention is needed, but the parents need to be reassured and advised to have periodic weight monitoring and follow up. If the child is maintaining oxygen saturations on room air and has no feeding issue, then outpatient management is appropriate. Feeding modifications including pacing, thickening of feeds and upright positioning while feeding should be advised.

Following are the consensus recommendations (2016) for management of laryngomalacia based on the clinical presentation

| Type of laryngomalacia | Clinical presentation | Management |

| Mild laryngomalacia | Having inspiratory stridor with no other symptoms or radiographic findings suggesting secondary airway lesion | 1-month symptom check, if stable or improving can extend to 3-6 month symptom check |

| Moderate laryngomalacia | Cough, choking, regurgitation, feeding difficulty | Start acid suppression therapy and consider feeding therapy/swallow evaluation |

| Severe Laryngomalacia | Apnea, cyanosis, failure to thrive, pulmonary hypertension, cor-pulmonale | Start acid suppression therapy and consider feeding therapy/swallow evaluation followed by supraglottoplasty in failed cases |

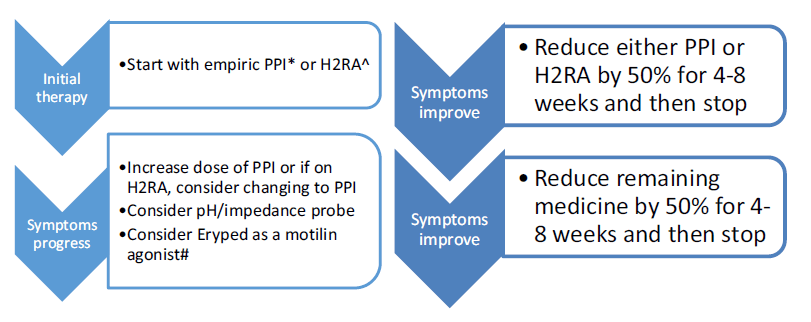

Though there is a lack of evidence for the role of anti-reflux medications in laryngomalacia, it is recommended to have acid suppression therapy especially in children with feeding difficulties and GERD symptoms. Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and a histamine-2 blocker (H2RA) therapy can be considered in such children, though the role of PPI in patients younger than 1 year is controversial as no PPI is FDA approved in this age group.

A step-up/step-down approach regimen is considered for managing acid suppression therapy. In a “step down” regimen, therapy can be started with both a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and a histamine-2 blocker (H2RA) and then weaned to a single therapy if the patient improves. PPIs are the preferred approach for children and adolescents, particularly when used empirically; once-daily dosing initially – morning dosing on empty stomach provides best acid suppression because H+ pump is less activated nocturnally, use evening dosing for nocturnal symptoms. H2RA decrease acid production by 40–60% and is well-tolerated and preferred for infants with non-life-threatening symptoms as H2RAs clinically better tolerated than PPIs. Low dose Erypred 200 (200 mg/5 ml) or Erypred 400 (400 mg/5 ml) at 1–2 mg/ kg/dose, 15 min before meals, up to 6× per day as a motilin agonist to increase smooth muscle contraction.

Alternatively, the infant can be started conservatively on a single therapy and “stepped-up” to dual-acid suppression if symptoms are not controlled. High-dose H2-blocker therapy (ranitidine 3 mg/kg, 3 times a day) can be started initially. Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) should be considered for refractory or breakthrough symptoms. They should also be implemented in patients who undergo surgical therapy, in the immediate perioperative and postoperative period until complete healing has occurred. Those with refractory symptoms may benefit from combined daytime PPI therapy and nighttime H2-blocker therapy.

According to the IPOG, 2016 recommendation, the therapy is maintained for at least 3 months after initiation and a wean should not be considered until a diet can be safely tolerated from an aspiration standpoint. In those children who are refractory to therapy, gastroenterology evaluation and/or pH/impedance probe testing needs to be considered. Additionally, prokinetic agents such as erythromycin ethyl succinate (Eryped) can be considered to improve gastrointestinal motility in refractory cases.

Persistence of symptoms despite maximal reflux suppression, especially in infants with hypotonia, should prompt a workup for neurologic causes prior to or concurrent to surgical management.

In children with an airway and/or feeding concern, consider admitting to the hospital or consider more urgent intervention. Surgical restoration of airway is needed for those.

- with severe symptoms (10% cases) – substantial sternal and intercostal retraction, pectus excavatum, failure to thrive, persistent stridor after 18-24 months, feeding anomalies, gastric reflux enhanced by increased negative intrathoracic pressure, obstructive sleep apnea, associated comorbidities (eg: cyanotic heart diseases, cor pulmonale, pulmonary hypertension)

- infant falling off growth curve after even after starting acid suppression therapy and feeding therapy/swallow evaluation.

- aspiration on FEES with evidence of respiratory compromise

The most common surgical procedure done is aryepiglottoplasty / supraglottoplasty. In this procedure, depending on the severity of airway collapse, the aryepiglottic folds are released from edges of the epiglottis, redundant mucosa and submucosal tissues are excised with part or all of the cuneiform cartilages. Care should be taken to preserve the bridge of mucosa, between arytenoids to prevent inter arytenoid scarring.

In children with co-existing neurologic disease, the benefit of improving airway obstruction by surgery must be weighed with the risk of worsening aspiration.

90% of children will get immediate relief from stridor following surgery. It is also found to reduce gastric reflux also. Complications were observed in 4% of children. These include laryngeal edema, granulation tissue formation, supraglottic stenosis, etc.

Lower success rates are seen in premature infants, children with congenital syndromes and with neurologic anomalies. Persistent laryngopharyngeal reflux or undiagnosed eosinophilic esophagitis may drive persistent laryngeal edema leading to continued laryngomalacia.

Patients with multiple severe comorbidities or multilevel airway obstruction are less likely to succeed with supraglottoplasty alone and may require tracheostomy.

In those children with persistent stridor even after surgery, other underlying hypotonic neurological disorders should be suspected.

Noninvasive ventilation (NIV) may be indicated in some infants with comorbid conditions or failing to respond to surgical management.

Prior to considering revision supraglottoplasty in failed cases, persistent reflux, eosinophilic esophagitis, obstructive sleep apnea, and other cardiac, neurologic, and pulmonary co-morbidities, etc need to rule out.

References

- Dobbie AM, White DR. Laryngomalacia. Pediatric Clinics. 2013 Aug 1;60(4):893-902.

- Garritano FG, Carr MM. Characteristics of patients undergoing supraglottoplasty for laryngomalacia. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2014 Jul 1;78(7):1095-100.

- Carter, J., Rahbar, R., Brigger, M., Chan, K., Cheng, A., Daniel, S. J., … Thompson, D. (2016). International Pediatric ORL Group (IPOG) laryngomalacia consensus recommendations. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 86, 256–261.

- Cooper T, Benoit M, Erickson B, El-Hakim H. Primary presentations of laryngomalacia. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2014 Jun 1;140(6):521-6.

- Wright CT, Goudy SL. Congenital laryngomalacia: symptom duration and need for surgical intervention. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 2012 Jan;121(1):57-60.

- Adil E, Rager T, Carr M. Location of airway obstruction in term and preterm infants with laryngomalacia. American journal of otolaryngology. 2012 Jul 1;33(4):437-40.

- Hartl TT, Chadha NK. A systematic review of laryngomalacia and acid reflux. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2012 Oct;147(4):619-26.

- Escher A, Probst R, Gysin C. Management of laryngomalacia in children with congenital syndrome: the role of supraglottoplasty. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2015 Apr 1;50(4):519-23.

- Faria J, Behar P. Medical and surgical management of congenital laryngomalacia: a case-control study. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Nov;151(5):845-51.

- Czechowicz JA, Chang KW. Catch-up growth in infants with laryngomalacia after supraglottoplasty. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Aug 1;79(8):1333-6.

- McCaffer C, Blackmore K, Flood LM. Laryngomalacia: is there an evidence base for management?. The Journal of Laryngology & Otology. 2017 Nov;131(11):946-54.

- Ayari S, Aubertin G, Girschig H, Van Den Abbeele T, Denoyelle F, Couloignier V, Mondain M. Management of laryngomalacia. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2013 Feb 1;130(1):15-21.