Acute calcific prevertebral tendinitis also is known as calcific retropharyngeal tendinitis or prevertebral calcific tendinitis is a self-limiting clinical condition due to calcification and inflammation of longus colli muscle and tendon. The condition was first described in 1964 by Hartley.

Longus colli is a bilateral paired neck flexor muscle, located in the prevertebral area, along with the longus capitis, rectus capitis anterior, and rectus capitis lateralis. The muscle originates from the transverse processes of C3–C5 and from the C5–T3 vertebral bodies. It inserts on the anterior arch of C1 and the C2–C4 vertebral bodies.

The clinical significance of the condition is that it mimics other serious medical emergencies like a retropharyngeal abscess, meningitis, and cervical disc herniation. Awareness of this condition can avoid unnecessary invasive interventions, increased costs, and delays that result from incorrect diagnosis and treatment.

Epidemiology

The condition affects mostly women, with a woman: men ratio of 3:2. The most common age groups affected are between the 3rd to 6th decade (range from 21-65 years) with a peak incidence at 41 years.

The mean annual crude incidence rate is 0.50 cases per 1,00,000 person-years, and the standardized incidence is 1.31 for the age-matched population.

Pathophysiology

Calcific tendinitis is considered to be a part of the spectrum of calcium hydroxyapatite deposition disease (CHAD). The condition occurs due to inflammation and calcium hydroxyapatite deposition in the muscle and tendon of longus colli.

The exact etiology and pathophysiology of calcium hydroxyapatite deposition is unknown. Various hypotheses, like repeated trauma, tendinous degeneration, have been proposed.

The currently accepted explanation for calcific tendinitis is by Oliva et al. Acute or chronic tendon injury results in an abnormal healing process mediated by macrophages, osteoclasts, and erroneously differentiated tendon-derived stem cells resulting in calcific tendinopathy. The further aseptic inflammatory response to the calcium deposition results in accumulation of reactive fluid within the retropharyngeal space.

Clinical features

The most common clinical symptoms are acute onset neck pain, drastically reduced range of neck movements, difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia), painful swallowing (odynophagia).

Other nonspecific symptoms like mild fever, a moderate-severe headache may also present.

On physical examination the patient may be febrile, the neck may be tender with a restricted range of movements. Most patients may have a bulging in the posterior pharyngeal wall.

Differential diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis needs to be considered and ruled out is a retropharyngeal abscess. It is very important to differentiate between these two diseases due to dramatic differences in management – retropharyngeal abscess is a life-threatening emergency while calcific tendinitis is a self-limiting condition.

Retropharyngeal abscess

The condition usually occurs in children, immunocompromised patients and those who have sustained penetrating neck trauma.

The clinical presentation is almost similar, but may also include higher-grade fever and trismus.

CT Imaging studies will show the presence of rim-enhancement, asymmetric retropharyngeal edema with air pockets suppurative retropharyngeal lymph nodes and absence of calcification in the longus colli muscle tendon.

Other differential diagnoses

Other differentials need to be considered are meningitis, cervical disc herniation, malignancy, and infectious spondylitis. Median atlantoaxial degenerative changes is a radiological differential diagnosis.

Investigations

Lab investigations

Blood investigations may demonstrate nonspecific signs of acute inflammation like mild leukocytosis, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and c-reactive protein (CRP).

Imaging studies are mandatory to rule out emergencies like a retropharyngeal abscess.

Plain radiographs

Plain X-rays are less sensitive than CT for these calcifications and may show only nonspecific prevertebral swelling.

Computed tomographic (CT) scan

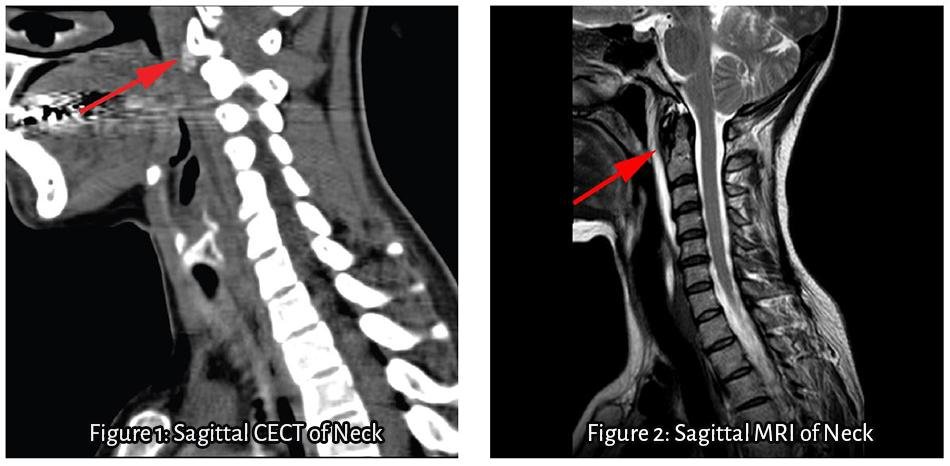

The characteristic findings in CT scan are amorphous, curvilinear (non-osseous) density along the longus colli muscle, particularly in the upper oblique fibers, at the level of C1 – C2 with associated soft tissue swelling.

Smooth expansion of retropharyngeal space due to edema or fluid may be present.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging

MR Imaging is not usually necessary for the diagnosis of calcific tendinitis. If done, it will help in differentiating an abscess from tissue edema. An abscess will demonstrate restricted diffusion and often have an enhancing wall following contrast administration while no restriction or rim enhancement is observed in case of edema.

Other characteristic findings in MRI are prevertebral edema and low-signal calcifications in the longus colli muscle tendons.

Treatment

Acute calcific prevertebral tendinitis is a self-limiting condition which requires only symptomatic treatment. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the first-line therapy and is continued for 2-3 weeks.

Other useful adjunct therapies which can be considered are corticosteroids, opioids, muscle relaxants and immobilization.

Prognosis of the condition is excellent.

References

- Al Balushi M, Varghese AM, Al Azri F, Al Abri R. It is always darkest before dawn. Oman medical journal. 2017 Sep;32(5):440.

- Patel TK, Weis JC. Acute neck pain in the emergency department: Consider longus colli calcific tendinitis vs meningitis. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017 Jan 25.

- Tamm A, Jeffery CC, Ansari K, Naik S. Acute Prevertebral Calcific Tendinitis. Journal of radiology case reports. 2015 Nov;9(11):1.

- Horowitz G, Ben-Ari O, Brenner A, Fliss DM, Wasserzug O. Incidence of retropharyngeal calcific tendinitis (longus colli tendinitis) in the general population. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Jun;148(6):955-8.