Main modality of treatment for oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma is surgery. Patients with advanced risk factors like margin positivity, perineural invasion, advanced disease, etc need postoperative radiotherapy.

Significant advances in terms of oncologic treatment (lasers, robotics) and outcomes have happened in the last three decades. But irrespective of these advancements 5‐year overall survival hasn’t significantly improved for advanced stages of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma when compared with other head and neck sites like oropharynx and larynx.

Conventional surgical resection

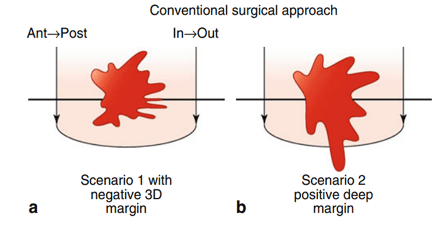

Conventional surgical treatment for oral lesions is circumferential wide excision. In a conventional method, dissection starts from mucosa and moves out to clear the involved soft tissues. This is also called the in-to-out approach.

The problem with circumferential resection is the potential of leaving some disease behind for large and deeply infiltrative tumors. By convention, a 1‐2 cm of macroscopically healthy margins around lesion the lesion is considered as adequate margin for wide resection. But this is not evidence-based and is not uniformly accepted.

This violates the primary aim of ablative cancer surgery; i.e to achieve negative margins in all directions. The presence of positive surgical margins in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma is 1.7 times more frequent than in any other subsites of the head and neck. Studies have shown that this positive margin on primary resection is significantly associated with local recurrence, regardless of the completeness of re-excision.

Another important pitfall of conventional resection is that the resection doesn’t follow anatomic planes.

The migration of tumor cells follows the path of least resistance. In the case of the tongue this is along and between the longitudinal muscle fibers, according to the orientation of the infiltrated muscle(s). This favors the fast progression of a tumor to the deeper tissue planes even up to hyoid.

Compartment surgery

Because of the above-mentioned limitations in conventional resection, a new concept of compartment surgery / anatomical resection was proposed by Calabrese et al. in 2011.

Compartments are defined based on the anatomy of particular subsite and pattern of disease spread.

The principle of compartment surgery is adopted from the surgical resection of sarcoma, i.e to remove the entire anatomical compartment in which the tumor is contained.

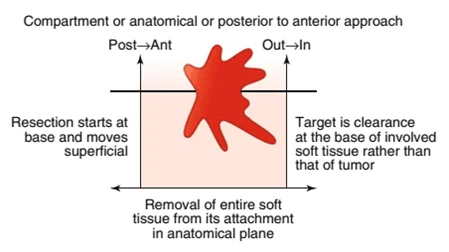

In compartment surgery, the entire involved soft tissue is removed from its farthest attachment at the base. The tissue is then mobilized from its base after ligating the neurovascular bundle at the entry point in the compartment. The resection then proceeds in an anterior direction (out to in) through soft tissues to end with mucosal cuts.

How compartment surgery performed?

The three main components of compartment surgery are.

- Identification of

- primary lesion and all of its potential pathways of spread,

- the distinct territory at risk for metastatic parenchymal structures between the primary tumor and the cervical lymphatic chain – muscular, neuro-vascular and glandular tissues;

- Radical and complete removal of this anatomical unit

- Preparation for a rational reconstruction

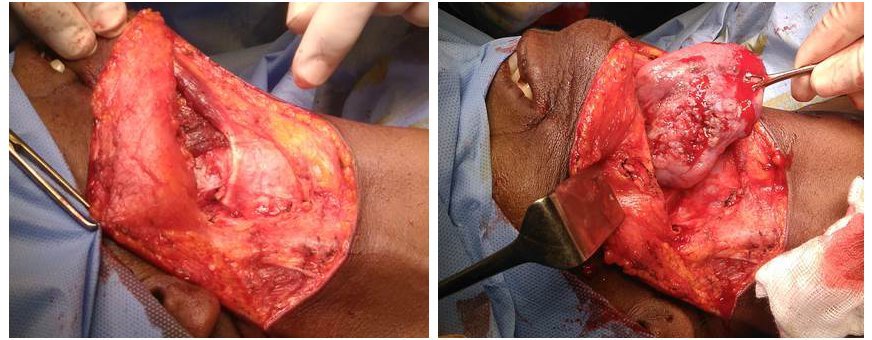

Considering an example of surgical resection of cancer tongue, the resection starts with a neck dissection. The approach to the tumor is then “from the bottom up”: from the neck to the tumor in a retrograde manner. Dissected contents of the neck are kept in continuity with the primary lesion throughout the approach to the tongue.

Detachment, of muscles (digastric, mylo-, genio-, stylo-hyoid and genioglossus) from their insertions and origin done. The ipsilateral lingual artery and hypoglossal nerve are ligated at the level of the hyoid bone. Identification of external carotid artery and ligation of lingual and facial artery done next which helps in reducing bleeding while resecting the tongue. The hyoglossus muscle is completely detached from hyoid bone.

Mucosal cuts are now made in the tongue. The tongue is split in the midline (if doing a hemiglossectomy). The tongue is then mobilized through neck via pull through (combined trans-oral and submandibular approach), or a transmandibular approach via a mandibulotomy can also be considered.

Now the entire hemi-tongue is resected from the level of the hyoid, creating a through and through defect between oral cavity and neck. The defect is later reconstructed with a pedicled or a free flap.

Why compartment surgery?

As mentioned above, the chance of a positive resection margin is high in conventional surgery. In compartment surgery entire involved soft tissue is removed from its origin to insertion which makes the chance of positive margin is negligible.

Depth of invasion (DOI) is the most powerful negative prognosticator in terms of loco‐regional control for oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. More the DOI, the tumor becomes more in close proximity to the neurovascular bundle, glandular structures, extrinsic muscles, etc. This favors potential tumor spread and results in an early lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and regional metastasis. Enbloc compartment resection removes the structures in close proximity together with the primary disease.

Tumor invasion of nerves and vessels progresses along a path parallel to the muscle fibers. In compartment resection, the dissection is always in an anatomical facial plane away from tumor margin. This enables the surgeon to achieve negative margins in a three dimensional and consistent manner.

Calabrese et. al are of the opinion that, when muscles are cut, even if partially, they become nonfunctional. This left behind nonfunctional remnant muscle remains always a tissue bed of potential microscopic tumor infiltration. This residual tissue may get fibrosis at a later stage affecting the mobility of residual tissue.

As the neurovascular bundle is ligated upfront at the start of the procedure, bleeding is always under control in the compartment surgery.

One of the most important reasons which favor compartment surgery is the failure of clearance of lingual lymph nodes in routine surgical resection. In conventional surgery, excision of the primary oral cavity disease and removal of neck nodes are done separately. This leaves behind the lingual lymph nodes, which are considered to be the first echelon nodes in tongue malignancies.

In a prospective study published in The Laryngoscope 2019, Fang et al observed the presence of lingual lymph nodes in 58 out of 239 patients. Out of which 33 were positive for metastasis. They found that metastasis to lingual lymph nodes was significantly related to adverse pathologic characteristics and lingual lymph node metastasis was an independent prognostic factor in oral cancers. They recommended routine dissection of lingual lymph nodes which could significantly decrease locoregional control.

Pros and cons of compartment surgery

Compartment resection is a new concept in oral cancers and as of today, no studies exist which studied the quality of life of patients undergoing compartment surgery. There exist no ‘head-to-head comparison’ studies that showed that recurrences are reduced with compartment resection.

According to the landmark article by Calabrese, compared to conventional surgery, compartment resection provides a 16.8% improvement in local disease control, 24.4% improvement in locoregional control and 27.3% improvement in overall survival at 5 years. Risk of death (for any cause) within 5 years from compartment surgery is about 1/3rd that of standard surgery.

Recently, Piazza et al studied the role of compartment resection in primary and salvage settings (previously treated either by surgery, chemo or radiotherapy). This was a single institute, retrospective study, among 45 patients of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma treated between Feb 2007 to Feb 2014. They concluded that compartment surgery is reliable in primary advanced oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma, but prognosis in terms of survival and local control still remains extremely poor even with compartment resection for salvage cases.

Fistula formation between oral cavity and neck, delayed healing, and radiation therapy postponement are common in patients undergoing compartment surgery.

Many surgeons consider doing compartment surgery for early lesions is like ‘destroying the whole forest’ to make a road through it. This procedure is associated with significant morbidity.

References

- Piazza C, Grammatica A, Montalto N, Paderno A, Del Bon F, Nicolai P. Compartmental surgery for oral tongue and floor of the mouth cancer: Oncologic outcomes. Head & neck. 2019 Jan;41(1):110-5.

- Szewczyk M, Golusinski W, Pazdrowski J, Masternak M, Sharma N, Golusinski P. Positive fresh frozen section margins as an adverse independent prognostic factor for local recurrence in oral cancer patients. The Laryngoscope. 2018 May;128(5):1093-8.

- Calabrese L, Giugliano G, Bruschini R, Ansarin M, Navach V, Grosso E, Gibelli B, Ostuni A, Chiesa F. Compartmental surgery in tongue tumours: description of a new surgical technique. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 2009 Oct;29(5):259.

- Tasche KK, Buchakjian MR, Pagedar NA, Sperry SM. Definition of “close margin” in oral cancer surgery and association of margin distance with local recurrence rate. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 2017 Dec 1;143(12):1166-72.

- Ong HS, Ji T, Zhang CP. Resection for oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma: a paradigm shift from conventional wide resection towards compartmental resection. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2014 Jun 1;43(6):784-6.

- Fang Q, Li P, Qi J, Luo R, Chen D, Zhang X. Value of lingual lymph node metastasis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Mar 12.

- Dutton JM Graham SM Hoffman HT. Metastatic cancer to the floor of mouth: the lingual lymph nodes. Head Neck 2002;24:401–5.

- Jia J, Jia MQ, Zou HX. Lingual lymph nodes in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and the floor of the mouth. Head & neck. 2018 Nov;40(11):2383-8.

- Calabrese L, Bruschini R, Giugliano G, Ostuni A, Maffini F, Massaro MA, Santoro L, Navach V, Preda L, Alterio D, Ansarin M. Compartmental tongue surgery: long term oncologic results in the treatment of tongue cancer. Oral oncology. 2011 Mar 1;47(3):174-9.