Total laryngectomy is a surgical procedure in which the entire larynx is removed by resecting the trachea and bringing out the lower stump as a respiratory opening in the anterior part of the neck (permanent tracheostomy) and thereby closing off the air passages to the mouth and nose. The patient permanently loses his/her natural voice as well as the sensation of smell.

Total laryngectomy is mostly done for malignancies involving the larynx. With the advent of improved surgical techniques, better post-op rehabilitation, and infection control, the focus has shifted to more conservative approaches that aim at both anatomical as well as functional preservation of the larynx.

The concept of organ preservation churned up a myriad of surgical as well as non-surgical (Chemo-radiotherapy) therapeutic interventions. Despite all this total laryngectomy still has a definite role in the management of advanced laryngeal malignancies.

Evolution of total laryngectomy procedure

The British surgeon Patrick Watson in 1866 has been credited in some articles of literature as being the first to perform a total laryngectomy. However, scrutiny of the medical records of the time clarifies that Dr. Watson only performed a tracheotomy for a patient with congenital syphilis and then for purposes of teaching and demonstration did a total laryngectomy post mortem.

The first in-vivo total laryngectomy was performed by Billroth in Vienna on 31st December 1873. It was a case of malignant growth in the larynx. The patient survived the procedure and went on to live for another 7 months. Although he developed significant pharyngocutaneous fistula he had resumed an oral diet and was even fitted with an artificial larynx, created by Gussenbauer.

In Italy, Enrico Bottini performed a total laryngectomy in 1875, followed a few years later by Azio Caselli in Reggio Emilia and Francesco Durante in Rome. The results from these initial cases showed that the intra op and immediate post-op complications elevated the mortality to about 50%.

In 1880 it was Gluck, along with his pupil Sorenson, who described a new method of performing the surgery. A similar approach was proposed at about the same time by Durante. They all agreed that there was a need to separate the respiratory tract as completely as possible from the digestive tract. Gluck initially proposed a two-staged procedure where the trachea is separated first and the larynx removed 2 weeks later. It was Sorenson in 1890 who finally came up with a single staged surgery, total laryngectomy as we know it today.

American surgeon George Washington Crile recognized the importance of the lymphatic system and distant metastasis. He advocated routine radical neck dissection with total laryngectomy in cases of malignancies. Martin and Ogura later standardized the steps involved in total laryngectomy with neck dissection.

In 1912 Francesco Durante’s student Gerardo Ferreri, who later became Director of Otology and Rhinolaryngology at Regia University in Rome, was the first otorhinolaryngologist to perform a total laryngectomy.

Total laryngectomy – Indications & Contraindications

Total laryngectomy is generally done for advanced malignancies involving larynx. The most common Indications & contraindications for total laryngectomy are discussed separately in another section.

Investigations needed prior to surgery

Prior to making the decision for total laryngectomy, the patient can be evaluated using one or more of the following:

For tumor workup:

- Digital X-ray soft tissue neck both anteroposterior and lateral views.

- Video laryngoscopy Tumour Workup

- Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck

- Micro laryngeal Examination with Biopsy

For metastatic workup (distant spread of the disease)

- Contrast-enhanced computed tomogram of Neck

- Ultrasonography of abdomen Metastatic Workup

- Thoraco-lumbar spine Radiographs

- Positron emission tomogram scan

To identify synchronous primary tumors (second primary tumors)

- Bronchoscopy

- Oesophagoscopy

- Barium swallow

Preoperative assessment

Firstly, the patient’s condition must be evaluated extensively using the various modalities available and as afforded by the patient. For malignant growths, a tissue diagnosis is absolutely essential. If total laryngectomy is selected as the best option for the patient – keeping in mind the above indications – the following factors need to be considered:

- Is the patient medically fit for general anesthesia (GA) – a cardiologist must certify that the patient’s cardiac status is stable and that he may undergo surgery under GA.

- Post total laryngectomy status puts immense stress on the respiratory system and patients with a poor respiratory reserve are poor candidates for laryngectomy.

- The patient should have adequate dexterity of hands/fingers to manage the Laryngectomy tubes.

- Any distant foci of sepsis should be sought for and dealt with before embarking on laryngectomy. Of these, most commonly, dental caries must be treated as well as any active dermatological conditions.

- Finally and probably most importantly the patient must be counseled to be prepared for the rigors of post total laryngectomy life.

- A written informed or if possible a video consent should be taken prior to the surgery. The various aspects of the surgery, complications and post-op rehabilitation should be discussed with the patient and relatives with emphasis on the permanent loss of voice.

- The anesthesia team should look for any airway difficulties and inform if tracheostomy is needed under local anesthesia (LA) – Care should be taken to site the skin incision at the intended site of tracheostomy stoma. This helps to avoid the Bipedicled bridge of skin between the skin flap and the tracheostomy site.

Surgical steps in total laryngectomy

Patient Position & Anesthesia

The patient is positioned in the supine position with the neck in a slight extension. This can be achieved by either placing a small sandbag beneath the shoulder or by moving the patient to the end of the table and using a head holder.

General anesthesia is given either by intubating the patient via an endotracheal tube (ET) or via the tracheostomy (flexo metallic ET tube).

The entire neck starting from the mandible down to the sternum and clavicle is painted with antiseptic – povidone-iodine and then spirit. The surgical field is draped and the preferred incision is marked out.

A Ryle’s tube is inserted prior to the surgery.

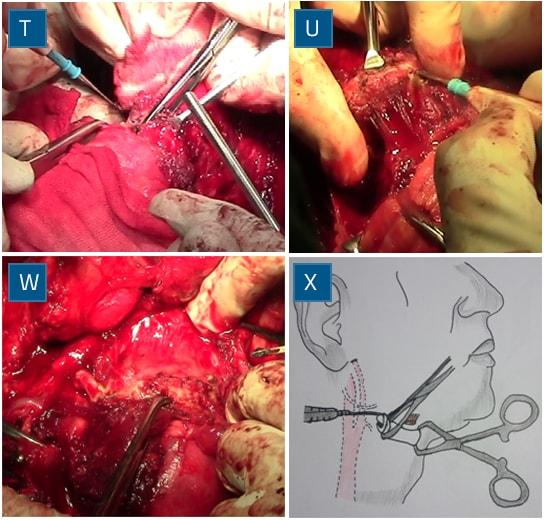

Incision in Total Laryngectomy

The choice of incision mainly depends on the personal preference of the surgeon, as well as factors like whether radical neck dissection is required or not.

The most commonly followed incision for total laryngectomy is the U-shaped Gluck – Sorenson incision starting from the mastoid on one side, going along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, intersecting at the level of cricoid in midline (2cm above sternal notch) and extending to the mastoid on the other side, including the tracheostome in the incision.

The Gluck-Sorenson incision allows maximum access to neck dissection with the same incision. Other incisions for total laryngectomy can be found out here.

The Tracheostomy

It has been proven that the incidence of stomal recurrence after total laryngectomy increases when the tracheostomy is done prior to the laryngectomy as a separate procedure for airway obstruction. Furthermore, as the time elapsed between the tracheostomy and the laryngectomy increases the chances of stomal recurrence also increases. Keeping these facts in mind it is always desirable to fashion the tracheostomy during the laryngectomy as a single procedure whenever possible.

The site of the tracheostomy is usually at the 2nd or 3rd tracheal rings. However, in case of a subglottic or tracheal involvement, the site may need to be moved further down keeping in mind the principles of oncologic resection.

There are a lot of minor variations in the procedures described in the literature. An attempt has been made to describe all of them here. The choice of procedure is mainly dependant on the personal preference and expertise of the surgeon.

Exposure

Firstly the incision site is injected with a vasoconstrictor usually adrenaline in 1:100000 dilution.

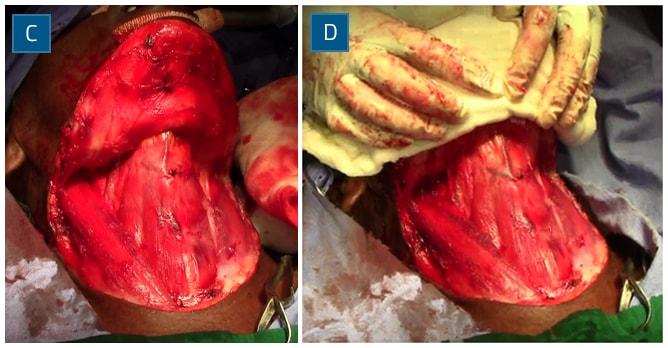

Using a 15 blade the skin incision is made and tissue dissected up to the subplatysmal plane.

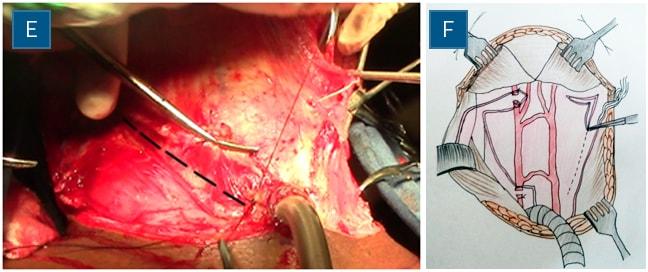

The subplatysmal flap is raised superiorly above the level of hyoid bone and inferiorly up to the level of the sternum and clavicular heads so that the entire larynx is visualized. The flap should contain skin, subcutaneous fat and platysma muscle. This ensures that the vascularity of the flap is maintained.

The deep cervical fascia is incised along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle creating the “outer tunnels”. The anterior jugular veins need to be clamped and ligated at this point. The omohyoid muscle is identified and cut to allow good exposure.

The strap muscles are identified and cut at the level of the hyoid and the inferior end is mobilized and kept to be used at the end of the surgery to fashion the stoma. The superior end is ligated and removed with the tumor. Some authors are of the opinion that the strap muscles should always be cut as low as possible in the neck to prevent stenosis of the final stoma.

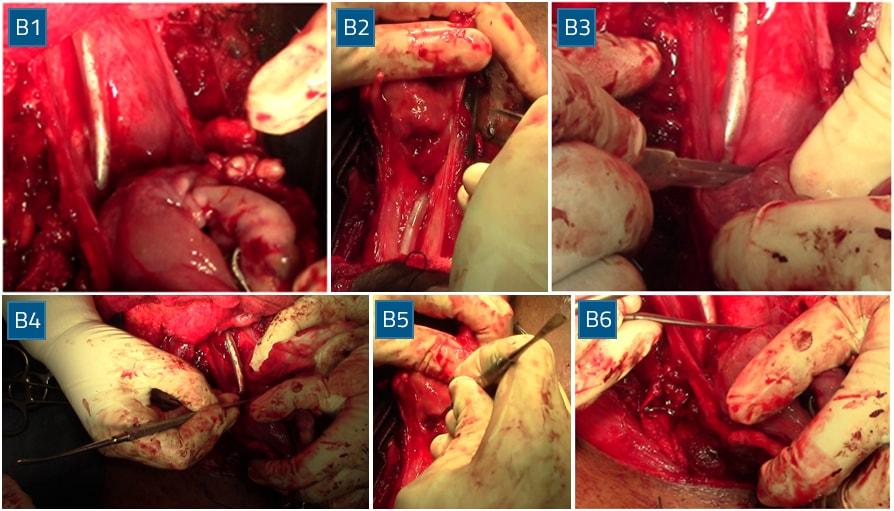

Thyroidectomy

Following the above steps on both sides, the thyroid gland can be readily identified.

How the thyroid is dealt with depends on the extent of the tumor. For unilateral tumors confined to the larynx, the contralateral lobe is preserved and the ipsilateral lobe may be removed. For bilateral extensive lesions invading the thyroid cartilage, those with subglottic extension more than 1 cm or those with extensive involvement of paratracheal or paralarayngeal lymphatics, a total thyroidectomy is warranted.

All attempts should be made to preserve the thyroid as much as possible to prevent post-op hypothyroidism or hypoparathyroidism.

Firstly the isthmus is identified and dissected off the trachea. It is cut between clamps and the ends ligated with heavy sutures. On the ipsilateral side the middle thyroid vein, superior and inferior thyroid pedicle are clamped, cut and ligated. The contralateral lobe is freed off its attachments to the trachea, from medial to lateral (to preserve blood supply), whilst the ipsilateral lobe is left alone and removed with the laryngectomy specimen. The superior pedicle on the side to be preserved may be sacrificed if necessary however the inferior pedicle must be saved. If at the end of the dissection the vasculature to the parathyroid seems poor then it maybe transposed into the neck musculature.

Skeletonisation of the Larynx

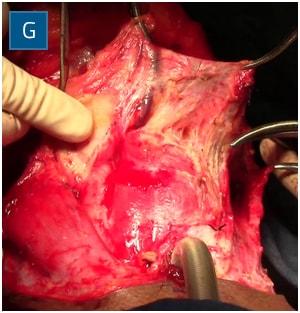

After the thyroid is out of the way the neck dissection may be completed and all necessary lymph nodes along with soft tissue may be removed. A “deep tunnel” is then created by blunt dissection in the plane between the carotid sheath and the larynx. Extending this tunnel superiorly will take us to the superior laryngeal pedicle at the level of the hyoid. This is identified and clamped bilaterally.

Once the superior laryngeal pedicle is secured, the larynx may be mobilized. The body of the hyoid is grasped using a towel clip and the suprahyoid muscles (mylohyoid, geniohyoid, digastric sling and hyoglossus) are disinserted. Once the central part is freed the hyoid bone is held using an Alley’s forceps and the region of the greater cornu is released on both sides. Here one must be careful not to injure the hypoglossal nerve and the lingual artery. This is done by retracting the hyoid so as to expose the tip of the cornu and staying as close to the bone as possible.

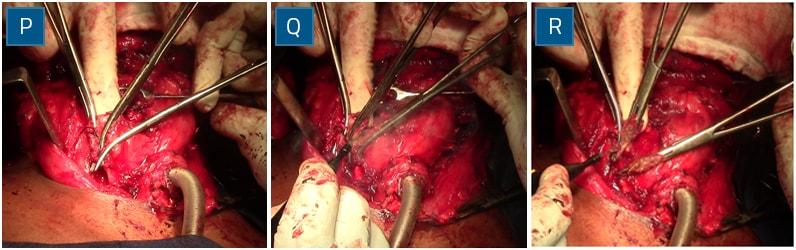

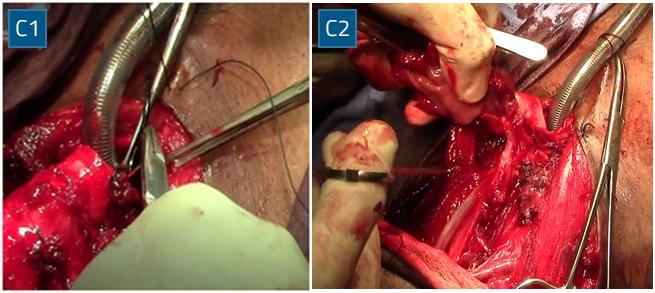

Pharyngotomy

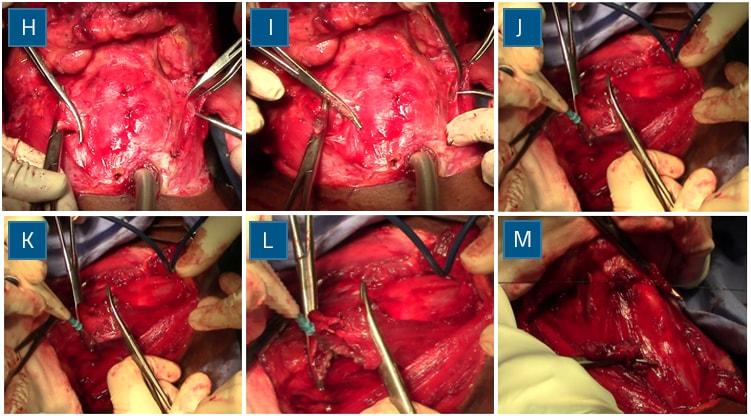

The mucosa over the epiglottis is then stripped off by blunt dissection and the epiglottis is identified and grasped using Alley’s forceps. It is important to preserve as much as mucosa as possible for pharyngeal reconstruction.

To avoid cutting through the tumor or its submucosal extension, the pharynx may be entered contralateral to the tumor. Tongue base involvement warrants a lateral pharyngotomy behind the thyroid cartilage. The extent of the tumor is inspected and a safe 2 cm margin of normal-looking mucosa is preserved with further cuts from below, progressing superiorly behind the thyrohyoid membrane, around the hyoid bone, and then transversely across the vallecula or tongue base.

If the tumor is confined below the level of the hyoid then the pharynx may be entered directly through the vallecula in the anteroposterior direction. Following the hyoepiglottic ligament allows the correct identification of the plane and prevents entry into the pre epiglottic space. Once the mucosa is opened the epiglottis can be identified and delivered using Alley’s forceps.

Craniocaudal Resection

The aryepiglottic fold is then cut close to the epiglottic side, thereby leaving ample pharyngeal mucosa for reconstruction. The thyroid cartilage is further angled and the attachments of the constrictor muscles are cut close to the cartilage from superior to inferior. This is continued on either side up to the apices of the pyriform sinuses.

A transverse cut through the post cricoid mucosa is then made. This incision connects the vertical incisions laterally. It is position behind the body of the cricoid lamina. Then by blunt dissection, the plane between the trachea and esophagus is identified and dissection continued up to the tracheostomy.

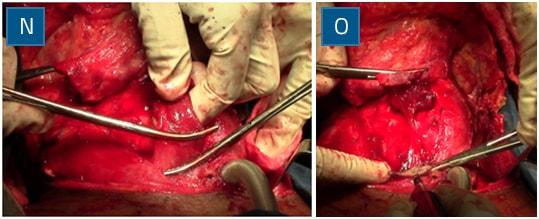

Laryngotracheal Separation

Once the trachea is separated from the oesophagus the tracheal rings are cut horizontally at the desired level. The incision is carried behind in a beveled fashion from anteroinferior to posterosuperior.

The ET tube can now be removed and a new laryngectomy or flexo metallic tube may be inserted via the lower stump and anesthesia delivered through it.

The lower stump must first be anchored to the skin before transecting the trachea completely.

The larynx is now totally free of all its attachments except for part of the post cricoid mucosa which is also separated. Once the specimen is out a thorough wash is given to the field.

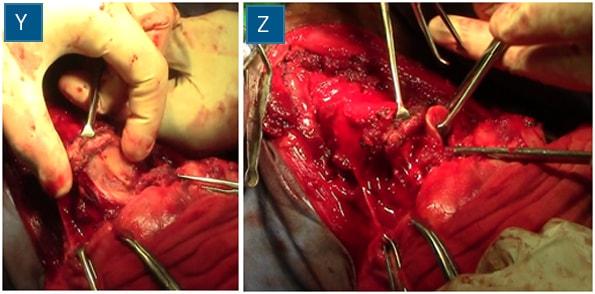

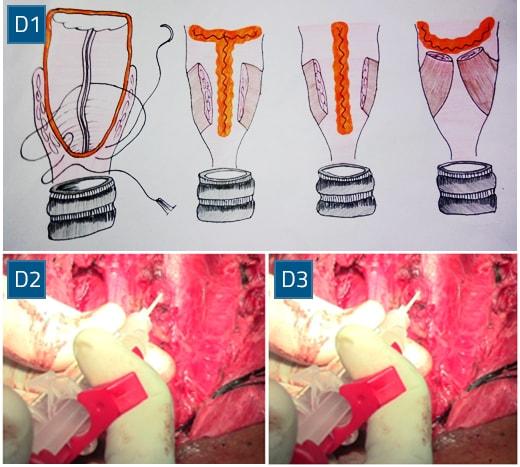

Pharyngeal Closure

It is important that the specimen is given for a frozen section biopsy to confirm negative margins. Then the defect in the pharynx needs to close.

The type of closure depends on the amount of pyriform sinus mucosa available. Usually, a ‘T’, vertical or horizontal closure is done. This step must be done with utmost care as a defect in the pharyngeal mucosa causes pharyngo-cutaneous fistula.

Care must be taken to ensure that the mucosal margins are inverted. Interrupted or running inverted sutures may be used.

Once the pharynx is closed a second wash is given and any defect identified. Tissue glue may be placed over the suture lines and allowed to set.

At this point, a tracheoesophageal stoma may be created for the insertion of a TEP voice prosthesis. In cases that are not irradiated previously, and the patient is counseled properly pre-op, the prosthesis is kept intraop. This gives the best results.

However, previous radiation to neck increases the chance for a pharyngocutaneous fistula and the prosthesis is best delayed till complete wound closure. Some surgeons also place the primary feeding tube through the potential stoma and after wound healing replace this with the prosthesis.

If the pharyngeal mucosa is not sufficient to give adequate closure then a repair using flaps must be considered. Either a myocutaneous flap, a muscle flap, or a microvascular free flap may be used. It is said that a remnant wall of a 1.5cm width is sufficient for closure without dysphagia.

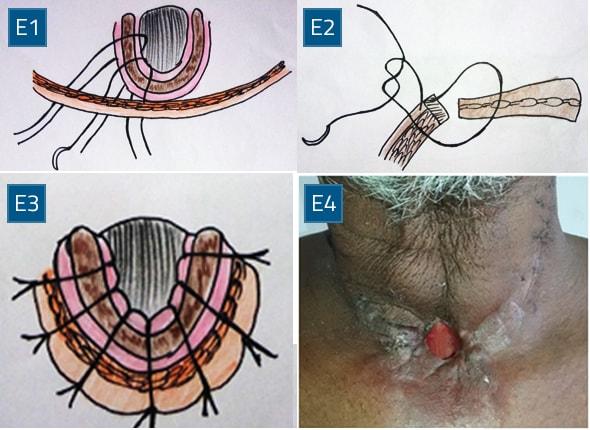

Stoma Creation

Following pharyngeal closure, a drain is kept and then the stoma is created.

Half mattress sutures with a large bite in the skin will pull the skin over the tracheal cartilage. This is done all around and the neck wound is closed in layers.

Absorbable sutures are used in the region of the stoma as removal may be difficult. The heads of the SCM may be cut to give rise to a flatter stoma and prevent stenosis. The muscle is then mobilized and secured on the prevertebral fascia between the carotid and pharyngeal closure. This potentially decreases the chance of a pharygocutaneous fistula and protects the carotids from saliva if it does occur.

Total laryngectomy Unedited Video

Post op care

The patient is shifted immediate post-op to an ICU for observation.

In our center, he/she is maintained on parenteral nutrition for the first 24 hours. The wound dressing is changed once every 24 hours. A cleaned and sterilized tube is changed each time. The drain is removed if the total collection in 24 hours is less than 20 ml for 2 consecutive days.

If the patient is stable, then the urine catheter is removed, and the patient made ambulant the very next day of surgery.

IV antibiotics are continued for about a week post-op. If there are signs of wound infection, then a culture sensitivity report is warranted and targeted antibiotics are changed.

The frequency of dressing may also be increased as needed.

The viability of the flap is assessed daily, and early changes noted and addressed accordingly.

The patient is advised to be NPO and not even allowed to swallow saliva till about a week. Ryle’s tube feeding may be started after 24-48 hrs.

After 7 days the neck sutures are removed except for around the stoma.

If the closure looks healthy then the patient is asked to take sips of liquid feeds like milk/water after 1 week. If there is no leak then the patient is started on oral feeds and the Ryle’s tube can be removed. In case of salvage total laryngectomy (history of prior irradiation to the neck) then oral feeds are delayed for about 2-3 weeks.

4 -6 weeks post-op, once the wound is completely healed the patient can be sent for post-op radiotherapy if required.

During the immediate post-op period the acute loss of voice and getting used to stoma care may have a profound effect on the patient’s psyche. The patient is counseled during this period.

Attention should be paid to parameters like Hemoglobin count, renal function tests, urine output, nutritional status, stoma care, humidification of air and suction clearance of secretions, maintenance of saturation and corrective measures initiated at the earliest.

If a tracheoesophageal prosthesis (TEP) is placed primarily then phonation exercises must be started early in the post-op period.

Total laryngectomy – Complications

Post total laryngectomy complications can be broadly divided into two, early and late complications.

Early Complications:

Drain Failure – Non-functional drains result in the collection of secretions under the flap, compromising its viability. The loss of vacuum may be due to leak in the pharynx, skin or stomal closure. It must be identified early and rectified.

Hematoma – This is a relatively rare complication of total laryngectomy. If present the patient must be taken back to the OT and clots evacuated. New drains must be inserted at this point.

Infection – If erythema and edema of the skin develop then subcutaneous infection should be suspected. The pus must be promptly drained under sterile conditions and sent for culture and sensitivity. The dead space between the neopharynx and skin flap is reduced by compressive dressing or antiseptic gauze packing. If the discharge persists, then a pharyngocutaneous fistula must be suspected or a chyle fistula should be ruled out if neck dissection is carried out.

Pharyngocutaneous Fistula – Poor pre-op nutritional status, advanced tumor stage, diabetes, pre-op radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy are all factors that significantly increase the chance of fistula. The fistula results from a closure defect through which saliva accumulates in the dead space between the neopharynx and skin flap.

A turbid copious drain and erythema and edema around the wound should arouse suspicion of fistula. It can be confirmed by methylene blue given to the patient orally or by gastrograffin swallow radiography.

Fistula is managed by regular antiseptic gauze packing as well as compression dressing to reduce dead space. The patient is kept NPO and not even allowed to swallow saliva. A salivary bypass procedure may be helpful in these cases. The tract may be attempted to be sterilized from inside out by asking the patient to swallow antiseptic solution few times daily – 10 mL of 0.25% acetic acid by mouth or an antibiotic or other antiseptic preparation three to four times daily. If conservative methods fail, then operative closure of the track needs to be considered.

An excellent option for fistula closure before complete epithelialization is a pedicled muscle flap (pectoralis, trapezius, or latissimus dorsi) slipped between the pharyngeal and skin defects. Such flaps endow excellent blood flow and antibacterial benefits to an avascular, infected bed. Control of esophageal reflux is also an important aspect of preventing and managing pharyngocutaneous fistula.

Wound Dehiscence – Wound dehiscence may accompany a tensioned skin closure, post-radiation state, wound infection, fistula, or poorly designed ischemic neck flaps. Local wound care should suffice for healing by secondary intention, but if the carotid becomes persistently exposed, vascularized muscle flap coverage is advisable.

Late Complications:

Stomal Stenosis – If the stoma is created as described earlier, stomal stenosis is uncommon. This approach can be used in revision as well.

In patients with small tracheas or a propensity for stenosis, women have a higher likelihood of fistula. Revision, when necessary, can be done with V-Y advancement flaps, Z-plasties, and a “fish-mouth” stomaplasty. Excision of cartilage remnants is preferable to radical excision and laryngectomy tube placement, but in some cases, prolonged use of a laryngectomy tube is required.

Pharyngoesophageal Stenosis and Stricture – When pharyngoesophageal stenosis or stricture is evident, tumor recurrence should be suspected; but once this has been ruled out by endoscopy and biopsy, outpatient dilation is usually an effective treatment. An adequate lumen (36 Fr) is necessary not only for swallowing and nutrition but also for tracheoesophageal speech production. If dilation is unsuccessful, flap reconstruction is preferable.

Hypothyroidism – Preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy plus hemithyroidectomy is usually sufficient to induce a low-thyroid state. Thyroid function tests every 1 to 2 months after completion of all treatment is indicated when supplemental thyroid medication is required.

Rehabilitation after total laryngectomy

The following are chief problems in a patient after total laryngectomy. Rehabilitation after total laryngectomy needs to address all these issues.

- Loss of speech: This will be the main concern for the patient. There are various options like esophageal speech, electronic larynx, tracheoesophageal speech, etc.

- Swallowing

- Tracheostoma problems

- Problems with glottal occlusion. e.g.: for weight-lifting

- Problems with airway diversion – e.g.: loss of smell perception (olfaction)

- Psychological/social problems.

- Total laryngectomy can also cause the end of employment and associated financial difficulties.

References

- Moretti A, Croce A. Total laryngectomy: from hands of the general surgeon to the otolaryngologist. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica: organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2000 Feb;20(1):16-22.

- Mohebati A, Shah JP. Total laryngectomy. Otorhinolaryngology Clinics An International Journal. 2010 Sep 25;2(3):207-14.

- CEACHIR O, HAINAROSIE R, ZAINEA V. Total laryngectomy–past, present, future. Maedica. 2014 Jun;9(2):210.

- Open access Atlas of Otolaryngology, Head & Neck Operative Surgery, Total Laryngectomy, Johan Fagan

- Head and Neck Surgery and Oncology, Jatin Shah, 3th Edition

- Scott Brown Otorhinolaryngology, Head & Neck Surgery, 7th edition

- Cummings Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 6th edition