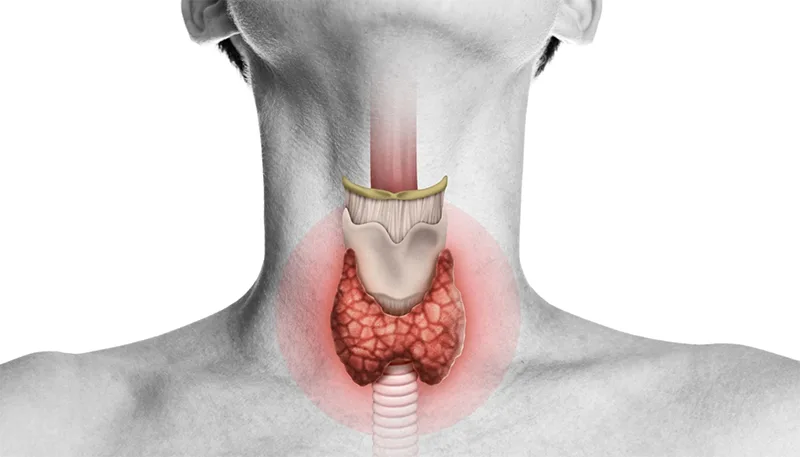

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis—also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis, chronic autoimmune thyroiditis, silent thyroiditis, painless thyroiditis, or historically as Struma lymphomatosa—is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in iodine-sufficient populations. The disease is characterised by autoimmune destruction of thyroid follicular cells through immune-mediated processes.

First described by Hakaru Hashimoto in 1912, it continues to be a central entity in endocrine and autoimmune diseases due to its complex interplay of immune-mediated thyroid destruction and evolving thyroid dysfunction.

Pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

The pathophysiology involves both cell-mediated and humoral immune responses. The thyroid gland becomes infiltrated predominantly by cytotoxic T cells, leading to follicular destruction, fibrosis, and gradual atrophy of the gland. Autoantibodies against thyroid peroxidase (TPO), thyroglobulin, and microsomal antigens are frequently elevated and serve as hallmarks for diagnosis.

The exact etiology of Hashimoto thyroiditis is still not fully understood but is thought to be a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- Genetic factors: Genetic markers such as HLA-DR3, HLA-B8, and CTLA-4 haplotypes are implicated in susceptibility.

- Environmental Factors: While genetics plays a key role, environmental influences are pivotal, especially given the less-than-complete concordance in monozygotic twins.

- Hygiene Hypothesis: Living in highly sanitized environments with reduced microbial exposure correlates with higher autoimmune disease rates, including Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

- Iodine Intake: Mild iodine deficiency appears protective to Hashimoto’s risk. Excess iodine increases the immunogenicity of thyroglobulin and raises Hashimoto’s risk. Significant deficiency can paradoxically also promote autoimmunity.

- Selenium Deficiency: Selenium-dependent enzymes like iodothyronine deiodinases and glutathione peroxidases protect the thyroid. Studies have shown that selenium supplementation reduces TPO antibodies and TSH levels—even in the absence of overt deficiency.

- Iron Deficiency: Thyroid peroxidase requires heme (iron). Iron deficiency impairs thyroid hormone production and worsens autoimmunity. Common in Hashimoto’s due to comorbid celiac disease, autoimmune gastritis, or menstrual blood loss.

- Vitamin D Deficiency: Vitamin D regulates immune tolerance. Low levels are linked to higher thyroid antibody titers.

- Gut Microbiome: Though influences immune homeostasis and thyroid hormone metabolism, recent studies show no significant microbiome difference in euthyroid individuals with or without thyroid antibodies.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis predominantly affects women, with an annual incidence of approximately 3.5 per 1000 women and less than 1 per 1000 men. The female preponderance suggests a hormonal or chromosomal influence, and familial clustering supports a genetic predisposition.

The incidence is found to increase with age also, with most cases found between ages 45 and 55 years. The incidence tends to be higher in countries with a lower prevalence of iodine deficiency.

It is often associated with other autoimmune disorders (part of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome) , including:

- Graves’ disease

- Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

- Vitiligo

- Coeliac disease

- Pernicious anemia

- Addison’s disease

Clinical Features of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

Goitre: (or enlargement of the thyroid gland) – Usually moderate in size, firm, and non-tender. The swelling may appear asymmetrical despite bilateral involvement of the gland. The swelling is slowly progressive, but sudden enlargement may suggest malignant transformation, especially primary thyroid lymphoma.

Thyroid Nodularity: Chronic inflammation of the thyroid gland in Hashimoto thyroiditis can lead to the formation of thyroid nodules. Approximately 20% to 30% of individuals with Hashimoto thyroiditis develop nodules, with incidence increasing with age. In some cases, the resulting thyromegaly—whether nodular or diffuse—may cause compressive neck symptoms such as dysphagia, dyspnea, dysphonia, chronic cough, or a sensation of pressure.

Thyroiditis: Thyroiditis can manifest in painless and painful variants. Most cases are painless. A few may be accompanied by throat pain. These cases are resolved within a few months.

Altered thyroid function: Thyroid function in individuals with Hashimoto thyroiditis can vary, ranging from euthyroidism and subclinical hypothyroidism to overt hypothyroidism and, occasionally, transient hyperthyroidism—each associated with symptoms such as menstrual irregularities, recurrent miscarriages, weight fluctuations, constipation, eye involvement and more.

Hashitoxicosis: A subset of patients may initially present with transient hyperthyroidism, termed Hashitoxicosis, before progressing to hypothyroidism. This thyrotoxic phase is due to release of preformed hormones from destructed follicles rather than increased synthesis.

Investigations

Thyroid Ultrasound

- Subacute phase: Enlarged, hypoechoic gland with hypervascular septae (mimicking Graves’ disease)

- Chronic phase: Small, atrophic, hypoechoic gland with no vascularity

- Suspicion of lymphoma: Patchy hypoechogenicity in an enlarged gland

Laboratory Tests

- TSH: Elevated (often the earliest abnormality)

- Free T4: Low or normal

- Antibodies: Thyroid peroxidase antibodies, antithyroglobulin antibodies, and antimicrosomal antibodies: Typically elevated

- ESR: Often raised, especially in active inflammation

- Serum Iron studies, Vitamin D levels are also checked

Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology (FNAC)

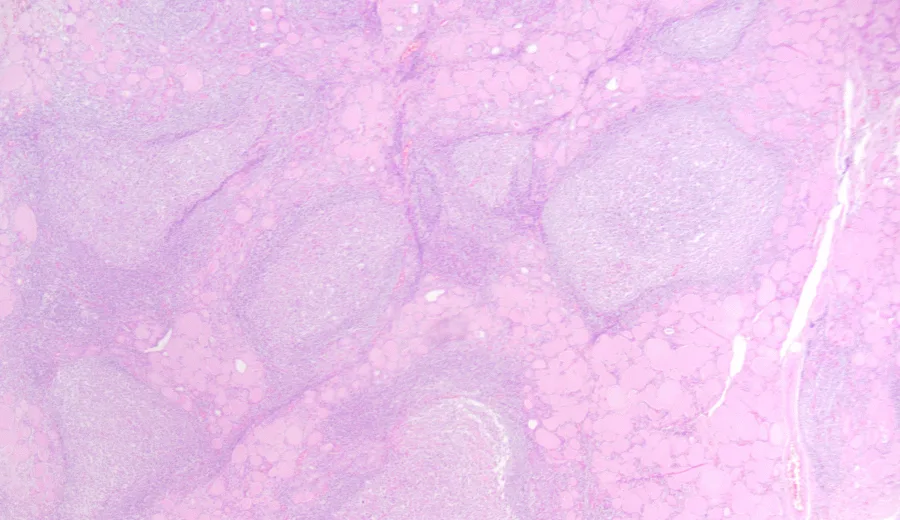

- Cytology will show significant lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration with destruction of thyroid follicles. There will be presence of fibrotic tissue, Askanazy (Hurthle) cells – oxyphilic epithelial cells with granular cytoplasm.

- Histopathological variants of Hashimoto thyroiditis have been described, including:

- Atrophic and fibrotic variants

- Riedel thyroiditis

- Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related thyroiditis

Radionuclide Scanning (RAIU)

- Early stages: Increased uptake

- Late stages: Low or absent uptake

- May show a heterogeneous pattern

- Gadolinium-67 scan: Can identify increased uptake in suspected thyroid lymphoma

CT/MRI Imaging

- CT scan: Diffuse enlargement; lymphoma shows low attenuation

- MRI: High T2 signal with low-intensity fibrotic bands; lymphoma appears hypointense on both T1 and T2 images

Treatment of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

Thyrotoxic Phase

- Typically self-limiting (up to 8 weeks)An Overvie

- Treated symptomatically with beta-blockers (e.g., propranolol)

Hypothyroid Phase

- May last months to years before stabilising

- Requires levothyroxine replacement therapy

- ~5% of subclinical hypothyroid patients progress to overt disease per year.

- Correction of iron deficiency, Vitamin D deficiency and selenium supplementation also is advised.

Surgical Intervention

- Reserved for large goitres causing compressive symptoms or cosmetic concerns

- Subtotal thyroidectomy may be considered in select cases

Prognosis

- ~5% of subclinical hypothyroid patients progress to overt disease per year.

- Individuals with Hashimoto thyroiditis are at risk for a rare thyroid malignancy: primary thyroid lymphoma. Though rare, primary thyroid lymphoma must be suspected in Hashimoto’s patients with sudden thyroid enlargement, compressive symptoms, or B symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats). Most are non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas, and early diagnosis dramatically improves outcomes.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis remains a clinical and diagnostic cornerstone in thyroidology, exemplifying the intersection of autoimmunity and endocrine dysfunction. With a spectrum that includes transient thyrotoxicosis, lifelong hypothyroidism, and rarely, malignant transformation, its management demands a multidisciplinary approach combining endocrinology, radiology, pathology, and sometimes surgery.