Sialolithiasis, or the formation of salivary stones, is a common disease affecting the salivary glands. The presence of stones (calculi) within the salivary gland ductal system or glandular tissue can result in significant discomfort and complications if untreated.

Epidemiology

Sialolithiasis is a prevalent disorder, more commonly seen in adults than in children. It has a slight female predominance. The submandibular gland is the most frequently affected, accounting for about 83% of cases, followed by the parotid gland (10%) and the sublingual gland (7%). Several factors make the submandibular gland more prone to stone formation, including:

- The Wharton’s duct is longer and has a wider diameter, which facilitates stone retention.

- The duct courses around the mylohyoid muscle, creating an angulation that opposes gravity.

- The submandibular secretions are more viscous and contain higher concentrations of calcium and phosphorus, predisposing to stone formation.

Pathology

The exact mechanism of sialolithiasis is still unclear. However, two main theories exist:

- Defective autophagosome migration through the ductal system may contribute to stone formation.

- Calcification of mucus plugs within the duct could lead to stone development.

Sialoliths are composed of organic and inorganic material, with a central core (medulla) that is primarily organic. Calcium phosphate is the predominant inorganic salt found in these stones. A shift in salivary pH or dehydration often precipitates the calcification process.

Clinical Features

Sialolithiasis is characterized by the formation of calculi, primarily within the ducts of the salivary glands. Key clinical features include:

- Pain and swelling, which are often exacerbated by eating or salivation (gustatory stimulation).

- The swelling is diffuse, rapid in onset, and typically non-tender, but can be accompanied by a burning sensation.

- Swelling usually subsides within hours.

- Palpable stones may be detected within the duct, especially in the submandibular region, whereas parotid stones are generally softer and less calcified, making them harder to feel.

- Prolonged cases can lead to acute suppurative or chronic non-specific sialadenitis (inflammation of the salivary gland).

- Some associations have been noted between sialoliths and systemic conditions like diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HT), chronic liver disease, and potentially nephrolithiasis (kidney stones).

Risk Factors for Sialolithiasis

Several factors contribute to the development of sialolithiasis, and identifying these can help in both prevention and patient management:

- Dehydration: Insufficient hydration leads to reduced saliva production, making the saliva thicker and more prone to stagnation, which can promote stone formation.

- Poor Oral Hygiene: Poor dental care can cause an increase in bacteria within the oral cavity, which may act as a nidus for stone formation or promote infections such as sialadenitis.

- Dietary Habits: A diet low in acidic foods can affect the pH of saliva, making it more alkaline and encouraging the precipitation of calcium salts. Conversely, diets high in calcium or dairy products can increase the risk of calcium-based stone formation.

- Medication: Certain medications like antihistamines, diuretics, or anticholinergics reduce salivary flow, increasing the likelihood of stone formation.

- Systemic Conditions: As mentioned earlier, conditions like diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic liver disease, and nephrolithiasis (kidney stones) have been linked to an increased risk of sialolithiasis. These associations suggest that metabolic or mineral imbalances in the body may also play a role.

Recognizing these risk factors is crucial for early intervention, particularly in patients with recurrent episodes of sialolithiasis.

Diagnosis

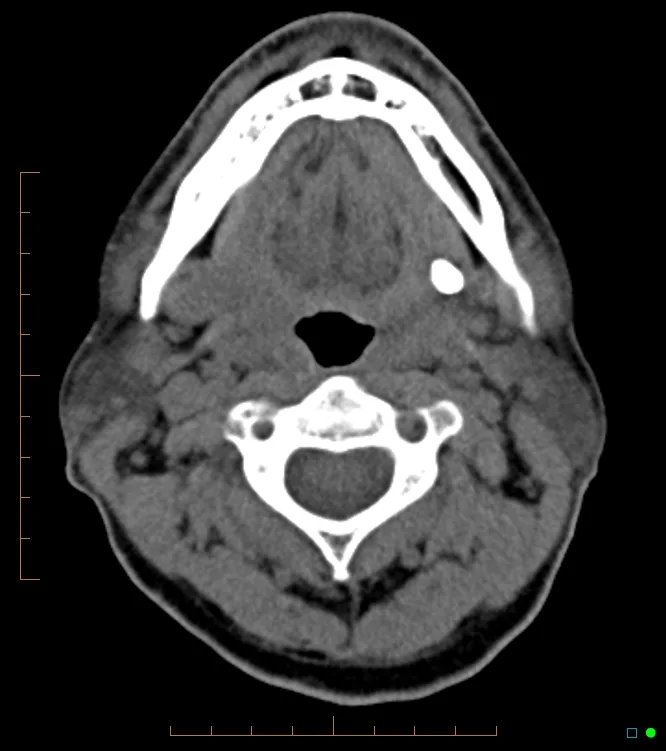

Diagnosis of sialolithiasis involves a combination of clinical examination and imaging studies:

- If the stone is clinically visible or palpable, further imaging might not be necessary.

- Plain radiographs (intraoral or occlusal view) can reveal radiopaque stones but may miss radiolucent ones, which are common in parotid sialoliths (around 30%).

- Ultrasound (USG) of the glands is a useful non-invasive tool that can detect both radiolucent and radiopaque stones, though its sensitivity is limited for stones smaller than 2 mm.

- Sialography can be employed but is technically challenging, particularly for submandibular and sublingual glands.

- CT scans are highly accurate for detecting stones, regardless of their size or location.

- MR sialography is extremely sensitive in demonstrating calcium deposits.

Treatment of Sialolithiasis

Management of sialolithiasis depends on the size, location, and symptoms of the stone.

- Asymptomatic stones: These can often be managed conservatively.

- Conservative management includes the use of:

- Sialagogues (substances that stimulate saliva production),

- Local heat application,

- Adequate hydration,

- Gland massage,

- Manual expression of small and accessible stones, particularly in the submandibular gland.

Surgical Treatment

- Stones located in the distal segment of the salivary duct can be surgically removed via a small incision on the floor of the mouth, followed by marsupialization of the mucosa to prevent stricture formation.

- For stones in the proximal duct or within the gland, complete removal of the affected gland may be necessary.

- Lithotripsy (breaking down stones using sound waves) has proven effective, especially for stones smaller than 7 mm in diameter. Lithotripsy may be enhanced by fluoroscopically guided basket retrieval or sialendoscopy.

- Sialendoscopy, a minimally invasive technique, has become increasingly popular for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. It can be combined with lithotripsy and balloon dilation of stenotic ducts.

- Laser lithotripsy or other forms of piezoelectric or electromagnetic lithotripsy are alternatives that have shown good results, with minimal side effects.

Post-Operative Care and Management

Post-operative care plays a significant role in ensuring successful recovery and preventing recurrence after treatment for sialolithiasis, particularly following surgery or lithotripsy. Key considerations include:

- Pain Management: Mild to moderate pain after procedures like sialendoscopy or lithotripsy is common and can be managed with NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs).

- Hydration and Sialogogues: Encouraging patients to stay hydrated and use sialogogues (such as lemon drops or chewing gum) helps prevent further stone formation and promotes healing by ensuring adequate salivary flow.

- Massage and Duct Care: Patients may be advised to gently massage the salivary glands to help dislodge any small residual fragments of stones. In some cases, patients might also be taught how to “milk” the duct to encourage saliva flow.

- Monitoring for Infection: Post-surgical infections, though rare, can occur. Patients should be instructed to watch for signs of infection, including fever, increased swelling, or purulent discharge, and seek prompt medical attention if these occur.

- Follow-up Appointments: Regular follow-ups, especially after lithotripsy or surgical removal, ensure that healing is progressing well and that there are no new or residual stones. Imaging studies like ultrasound or sialography may be used in these follow-ups to ensure the ducts remain clear.

Recent Advances in Treatment

Technological advances have significantly improved the management of sialolithiasis, offering less invasive and more effective treatment options. Some of the notable recent developments include:

- Sialendoscopy-Assisted Surgery: Sialendoscopy has gained prominence not only for diagnosing but also for treating sialolithiasis. The use of fine endoscopes allows for the visualization and retrieval of stones without the need for major incisions. This gland-sparing approach reduces recovery time and preserves salivary function.

- Balloon Dilation: This technique, often combined with sialendoscopy, can help to dilate narrow or stenotic ducts following stone retrieval, minimizing the risk of recurrence and promoting normal saliva flow.

- Robotic-Assisted Gland-Sparing Surgery: For larger or more posteriorly located stones, robotic surgery offers a precise, minimally invasive option. The ability to make small incisions and maneuver around vital structures reduces the need for complete gland removal, preserving salivary function while achieving a high success rate.

- Newer Lithotripsy Techniques: Laser lithotripsy and piezoelectric lithotripsy continue to evolve, with higher success rates and reduced complications. The advancements in lithotripsy devices have made the procedure more comfortable and efficient for breaking up larger stones into smaller, passable fragments, often without the need for general anesthesia.

Prevention of Sialolithiasis

While there is no guaranteed way to prevent sialolithiasis, the following measures may reduce the risk or recurrence:

- Adequate Hydration: Ensuring that patients stay well-hydrated helps maintain a normal salivary flow, reducing the risk of stone formation due to saliva stagnation or concentration of salts.

- Sialagogues: Chewing sugar-free gum, lozenges, or consuming acidic foods (like lemon) that stimulate saliva production can help keep the ducts clear.

- Good Oral Hygiene: Regular dental check-ups and maintaining good oral hygiene reduce bacterial load in the mouth, decreasing the likelihood of infection or stone formation.

- Avoiding Risky Medications: If possible, alternatives to medications that reduce salivary flow should be considered, especially for patients with recurrent sialolithiasis.