Inverted papilloma is a rare, benign but locally aggressive neoplasm that arises in the Schneiderian epithelium which lines the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses.

It is also known as Ringertz tumor, Schneiderian papilloma, Cylindroma and Benign papilloma of the nasal cavity.

Inverted papilloma is the second most common benign tumor of the nose, after ossifying fibroma, and is the most common cause for a surgical indication of benign nasal tumors.

History

- 1854 – Ward described the macroscopic features of papilloma of nose and used the word “papillomatous neoplasm”.

- 1855 – Billroth used the term “villous carcinoma” to describe inverted papilloma.

- 1883 – Hopmann used the terms “hard and soft papilloma” to ascertain the stoma : epithelium ratio.

- 1935 – Kramer and Som used the term “genuine papilloma” of the nasal cavity.

- 1938 – Ringertz coined the term “inverted papilloma”.

- 1966 – Berendes termed it as “malignant papilloma”.

- 1971 – Hyams described the three histological types – Papillary and exophytic/fungiform papilloma, Inverted form, Oncocytic / Cylindrical types

- 1981 – Stammberger first reported endoscopic treatment of inverted papilloma.

- 1987 – Batsakis used the term ‘inverted Schneiderian papilloma”.

- 1992 – Kashima et al suggested HPV association

- 1996 – Michaels regarded the three types of nasal papilloma as three completely distinct entities.

- 2005 – Eggers considered these three types of nasal papillomas as hybrid lesions.

Etiopathogenesis

The lining mucosa of the nose and paranasal sinuses is unique embryological in the sense that it is derived from the ectoderm, in contrast to the lining epithelium of laryngo-bronchial tree which is derived from endoderm. This special mucosal lining of the nose and paranasal sinuses is known as the Schneiderian membrane.

Papillomas arising from the Schneiderian membrane is very unique in that they behave like neoplasms, and are found to be growing inwardly – hence the term inverted papilloma.

The stimulus for this papilloma formation and proliferation is unknown. Human papillomavirus (HPV) has been implicated as a causative factor for this, though its exact role is controversial. HPV serotypes 6, 11, 16 and 18 are found to be associated with sinonasal inverted papilloma. Based on the potential to turn malignant, HPV-6 and -11 are regarded as low-grade risk types, and HPV-16 and -18 are regarded as high-grade risk types. Coinfection with Herpes simplex virus (HSV) may also interact with Human papillomavirus to cause inverted papilloma.

Other suggested causes could be chronic inflammation, smoking, allergy and occupational exposure to welding, organic solvents, and noxious agents.

Immuno-histochemistry studies have shown that, Metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) enzyme involved in tissue remodeling events were significantly increased in the lamina propria adjacent to the hyperplastic epithelium in inverted papilloma. In another study, Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) and its receptor, “c-Met”, were found to be increased in patients with inverted papilloma compared with controls, suggesting that they may be related to proliferation of inverted papilloma.

Molecular studies have identified down regulation of p53, p21 tumor suppressor genes in inverted papilloma with malignant transformation. Genetic testing for mutation of these genes may help in predicting maligant transformation of sinonasal papilloma.

Epidemiology

Inverted papillomas account for approximately 0.5-5.0% of all sinonasal tumors with an annual incidence of 0.5 to 1.5 cases per 1 lakh population.

The disease is most frequently seen in white males, 40-60 years of age with a mean age of presentation 50 years.

There is a significant predilection for males (with a male:female ratio of approximately 3-5:1.

Clinical features

Most common symptoms of inverted papilloma are unilateral nasal obstruction associated with watery nasal discharge or nasal bleeding. Due to the location, impairment of normal drainage of the maxillary antrum is common, the patient will have clinical features of sinusitis also. Other symptoms are anosmia (loss of smell), epiphora (watering from eyes), numbness over the cheek, hyponasal speech, etc.

The patient may have orbital symptoms like proptosis if lamina papyracea is breached.

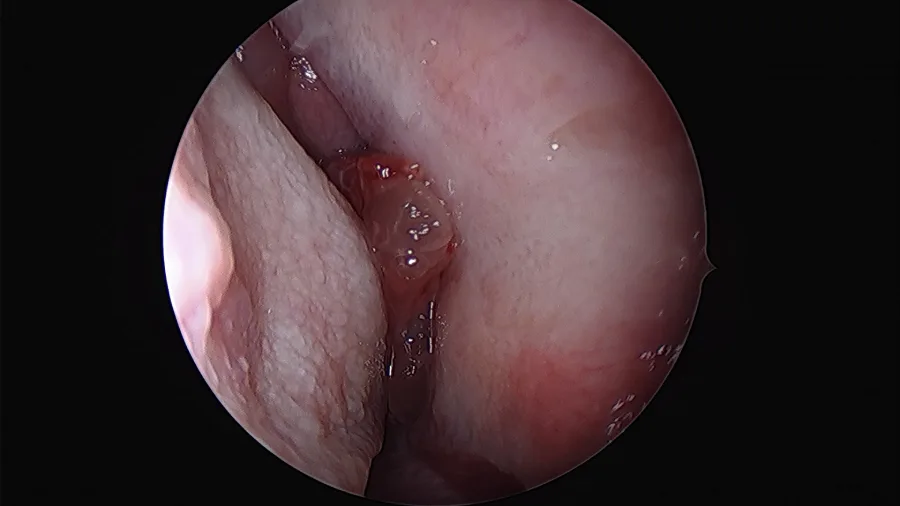

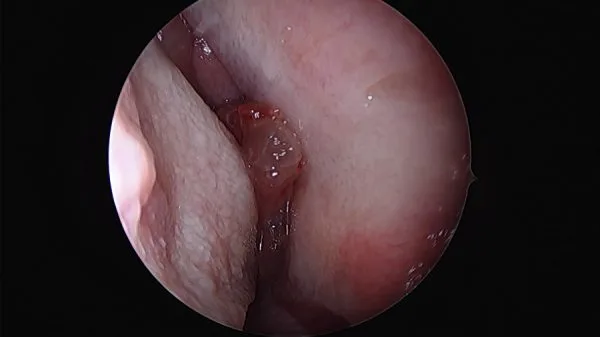

Clinical examination, usually by nasal endoscopy, will reveal a fleshy mass in the nasal cavity. Sometimes papilloma may occur behind a sentinel nasal polyp.

Commonly papilloma arises on the lateral wall of the nasal cavity, most frequently related to the middle turbinate and maxillary ostium, although they are seen elsewhere in the nasal passage. As the mass enlarges it results in bony remodeling and resorption and often extends into the maxillary antrum. Maxillary sinus is the second most common site after lateral nasal wall followed by other sinuses.

Differential diagnosis

Other sinonasal diseases that may mimic inverted papilloma in the clinical presentation are sinonasal carcinoma, sinonasal polyps, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (JNA), olfactory neuroblastoma and paranasal sinus mucocele, etc.

Investigations

Rigid nasal endoscopy: Rigid nasal endoscopy with biopsy is the investigation of choice for inverted papilloma. As mentioned before, endoscopy will reveal irregular pale, fleshy polypoid masses of variable consistency, pink in color, with a tendency to bleed.

X-rays: Xrays of the nose and paranasal sinuses no longer has a significant role play in the assessment of sinonasal disease. If obtaining, the most common finding is that of a nasal mass with associated opacification of the adjacent maxillary antrum. A chest radiograph is obtained for patients with associated squamous cell carcinoma.

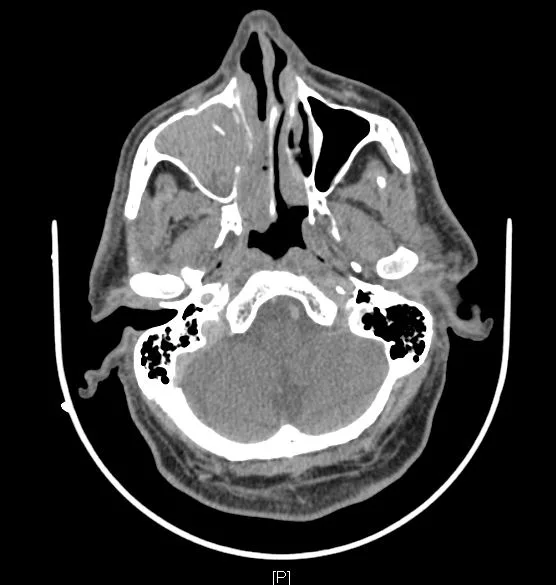

Computed tomography (CT) scan of nose and Paranasal sinuses with contrast medium: CT Scan features are largely non-specific, but it helps to assess the extent of the lesion and to stage the disease. CT demonstrates a soft tissue density mass with some post-contrast enhancement. As the mass enlarges bony resorption and destruction may be present, similar to those seen in patients with squamous cell carcinoma. Calcification is sometimes observed. The location of the mass is one of the few clues toward the correct diagnosis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI of inverted papilloma has a characteristic appearance – streaky delineation with convoluted cerebriform patterns on both T2 and contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images. MRI is the imaging of choice in follow-up for post papilloma removed patients.

Biopsy and histopathological examination: Histopathologically nasal papillomas show three architectural patterns (WHO classification). Sometimes there may be a combination of these histological patterns.

- Papillary and exophytic/fungiform/septal papilloma: This histology is commonly seen in papillomas arising in the nasal septum. There will be epithelial proliferation over a thin core of connective tissue. Inversion of epithelial masses is usually not present.

- Inverted form: This pattern is often observed in tumors occurring in the lateral wall of the nose and sinuses. There will be ribbons of respiratory epithelium enclosed by the basement membrane which grows into underlying stroma. Unless malignant transformation happens, there won’t be a breach in the basement membrane. The predominant cell type is epidermoid in nature. Intercellular bridges can be clearly demonstrated.

- Oncocytic / Cylindrical: Rarely the papilloma may be composed entirely of cylindrical cells, and hence this subtype is also called cylindrical cell / columnar cell papilloma.

| Comparison of essential features of the 3 types of sinonasal papilloma | |||

| Inverted papilloma | Exophytic papilloma | Oncocytic papilloma | |

| Frequency | Most common | Second most common | Least common |

| Location | Lateral nasal wall / paranasal sinus | Nasal septum | Lateral nasal wall / paranasal sinus |

| Male to female ratio | 2 – 3:1 | 10:1 | 1:1 |

| Most common age of presentation | 5th to 6th decades | 3rd to 5th decades | 5th to 6th decades |

| Association with human papillomavirus (HPV) | High risk HPV, Low risk HPV | Low risk HPV | No association |

| Architectural pattern | Endophytic (inverted) | Exophytic (filiform) | Exophytic or endophytic |

| Epithelial lining | Squamous, transitional or respiratory | Squamous, transitional or respiratory | Oncocytic |

| Molecular alterations | EGFR activating mutation | None reported | KRAS mutation |

| Risk of malignant transformation | 5 – 15% | ~0% | 4 – 17% |

Genetic testing: Role of genetic testing in inverted papilloma is theoretical only at present. Testing patients with inverted papillomas for p21, p53, and HPV may screen out those at risk for developing dysplasia or squamous cell carcinoma.

Classification and Staging of Inverted papilloma

There is no accepted staging system for patients with inverted papilloma. The one proposed by Krouse et al is most commonly followed. Krouse staging system and other staging systems for inverted papilloma are tabulated below.

| Krouse staging system | ||

| T1 | Tumor totally confined to the nasal cavity, with no extension into sinuses or any extra nasal structure. No concurrent malignancy | |

| T2 | Tumor involving osteo-meatal complex, ethmoid sinus, and/or medial part of the maxillary sinus, with/without nasal cavity. No concurrent malignancy | |

| T3 | Tumor involving any wall of the maxillary sinus (except medial wall), sphenoid sinus, and/or frontal sinus with/without the involvement of medial maxillary sinus, ethmoid sinus or nasal cavity. No concurrent malignancy | |

| T4 | All tumors with extra nasal / extra sinus extension (orbit, intracranial or pterygomaxillary fissure). All Tumors with concurrent malignancy | |

| Han staging system | ||

| T1 | Tumor limited to the nasal cavity, lateral nasal wall, medial maxillary sinus, ethmoid sinus or sphenoid sinus | |

| T2 | Tumor with extension lateral to the medial maxillary wall. | |

| T3 | Tumor with extension into the frontal sinus | |

| T4 | Tumor with extension outside paranasal sinuses (orbit / Intracranial). | |

| Olkawa staging | ||

| T1 | Tumor limited to the nasal cavity | |

| T2 | Tumor limited to ethmoid sinus and/or medial and superior maxillary sinus | |

| T3 | Tumor involves lateral, inferior, anterior, or posterior walls of the maxillary sinus, sphenoid sinus or frontal sinus | |

| T3a | Without extension to frontal sinus or supraorbital recess | |

| T3b | Involving frontal sinus or supraorbital recess | |

| T4 | Tumor extends outside sinonasal cavity (orbit/intracranial) or associated malignancy | |

| Cannady staging | ||

| Type A | Tumor confined to the nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus or medial maxillary sinus | |

| Type B | Tumor with involvement of any maxillary wall (other than medial), frontal sinus or sphenoid sinus | |

| Type C | Tumor with extension outside paranasal sinuses. | |

| Kamel classification | ||

| Type 1 | Tumor originating from the nasal septum or lateral nasal wall | |

| Type 2 | Tumor originating from the maxillary sinus | |

| Anatomic classification – according to its site of occurrence | ||

| Lateral wall | Tumor originating from the nasal septum or lateral nasal wall (multiple sites – floor, roof of nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses and nasolacrimal duct). | |

| Septal papillomas | Remain confined to the nasal septum and may very rarely involve the roof and floor of the nasal cavity | |

Treatment of inverted papilloma

Treatment for inverted papilloma is primarily by surgical resection, which provides a cure in most of the cases. Aim of the surgery is the complete eradication of the disease in the first attempt itself. Remnants if any will cause recurrence of the lesion.

Surgical removal of the tumor can be done via a lateral rhinotomy approach, midfacial degloving approach, a subcranial approach or an endonasal endoscopic approach.

With the advent of the nasal endoscopes, other radical surgical approaches become obsolete. The first report on endoscopic treatment of inverted papilloma dates back to 1981, when Stammberger documented 15 patients treated by a purely endoscopic approach.

Three types of endoscopic resections are currently practiced for endonasal endoscopic removal of inverted papilloma.

- Type I resection is indicated for inverted papillomas that involve the middle meatus, ethmoid, superior meatus, sphenoid sinus, or a combination of these structures; even lesions that protrude into the maxillary sinus without the direct involvement of the mucosa are amenable to this approach.

- Type II resection corresponds to an endoscopic medial maxillectomy, is indicated for tumors that originate within the nasoethmoid complex and secondarily extend into the maxillary sinus or for primary maxillary lesions that do not involve the anterior and lateral walls of the sinus. The nasolacrimal duct can be included in the specimen to increase the exposure of the anterior part of the maxillary sinus.

- Type III resection, also known as the Sturman-Canfield operation or endonasal Denker operation, entails removal of the medial portion of the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus to enable access to all the antrum walls.

If the mass is huge then a combined approach with a lateral rhinotomy may be needed for complete removal. Endoscopic resection is contraindicated in inverted papilloma with massive skull base erosion, intradural extension, intra-orbital extension, abundant scar tissue from prior surgery, and/or associated squamous cell carcinoma.

Along with the removal of the tumor, it is mandatory to remove the periosteum also from which the tumor is arising in order to eliminate potential microscopic lesions that may be present in the bone. The operation should end with the creation of a largely marsupialized cavity which will give wide access during follow-up for periodic endoscopic inspection.

Inverted papilloma is notorious for recurrence even after complete surgical removal of the mass. In olden days reoccurrence rates were higher between 0-78 % because of incomplete removal. Now, recurrence rates are below 10%. Other than incomplete removal, cigarette smoking is found to be associated with higher rates of recurrence. The majority of patients who develop a local recurrence can be successfully salvaged with additional surgery.

Surgically unresectable masses and masses that have undergone malignant transformation should be subjected to irradiation. Radiotherapy techniques and dose fractionation schedules are essentially the same as those used for carcinomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses.

Malignant transformation in Inverted papilloma

Inverted papilloma is associated with squamous cell carcinoma in approximately 5 percent of cases. Carcinomatous transformation is common in tumors arising in the lateral wall of the nasal cavity than those arising in the nasal septum.

Normally keratinization is rare in inverted papilloma. Excessive keratinization and a breach in the basement membrane should prompt the pathologist to have a diagnosis of malignant transformation.

Malignant transformation of inverted papilloma is found to have multiple histologies. Non-keratinising squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type, seen in approximately 11% of cases followed by the keratinizing type. Less frequently other malignant histologies including mucoepidermoid carcinoma, verrucous carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma seen.

References

- Mendenhall, W. M., Hinerman, R. W., Malyapa, R. S., Werning, J. W., Amdur, R. J., Villaret, D. B., & Mendenhall, N. P. (2007). Inverted Papilloma of the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses. American Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30(5), 560–563.

- Wright JM, Vered M. Update from the 4th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumours: odontogenic and maxillofacial bone tumors. Head and neck pathology. 2017 Mar 1;11(1):68-77.

- Wang MJ, Noel JE. Etiology of sinonasal inverted papilloma: A narrative review. World journal of otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. 2017 Mar 1;3(1):54-8.

- Vrabec DP. The inverted Schneiderian papilloma: a 25-year study. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:582– 605.

- Phillips PP, Gustafson RO, Facer GW. The clinical behavior of inverting papilloma of the nose and paranasal sinuses: report of 112 cases and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:463– 469.

- Lawson W, Kaufman MR, Biller HF. Treatment outcomes in the management of inverted papilloma: an analysis of 160 cases. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1548 –1556

- Krouse JH. Development of a staging system for inverted papilloma. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:965–968

- Tomenzoli D, Castelnuovo P, Pagella F, et al. Different endoscopic surgical strategies in the management of inverted papilloma of the sinonasal tract: experience with 47 patients. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:193–200.